Watercress and the witch

I remember well my mother and grandmother descending below the roadway to pick from the dense thicket of watercress.

Jairus, 3 October 2025

I remember well my mother and grandmother descending below the roadway to pick from the dense thicket of watercress. It was an annual tradition in the spring to get the plant at its most tender. Watercress grows lushly in clean springs throughout the Pennsylvania Dutch country. The plant is full of vitamins and, coupled with its peppery taste, was a great way for our ancestors to waken the body after a long winter. In 1777, General Peter Muhlenberg advised his troops at the winter encampment at Valley Forge to eat freely of the watercress, convinced of its healing properties.

Our watercress crop was in a cool spring that fed into Hosensack Creek along Limeport Pike. My grandparents rented a home there back in the 1930s. Far more interesting to us kids than picking watercress were the stories of the witch who lived next door. In my childhood “the witch’s house” looked the part — it was dilapidated, the shattered glass windows gave an ominous view into the dark interior. Each year, we waited anxiously to pass the witch’s house and see just how far into spookiness it was collapsing.

Watercress growing in a fresh spring near Hosensack Creek

Then one year the witch’s house was gone. It had burned to the ground, erasing its existence but from our memory. As we learned later, the elderly woman who lived there when my aunts and uncles were small was not a witch — just a recluse who didn’t want them playing in her yard. She wore a witch’s mask to frighten them away and so the family lore grew, captivating well into my generation, both afraid and intrigued by the witch whose memory loomed large over the annual watercress harvest.

Drawn thread work

Making lace can be extremely time-consuming.

Justina, 26 September 2025

Making lace can be extremely time-consuming. The most “sophisticated” way is through traditional needle lace. With a grounding thread, you create a design and then create a web of thread in the open spaces with a variety of decorative open stitches. Another way is through bobbin lace, where pairs of bobbins wound with thread are twisted and knotted in pattern to create lace. Both ways basically create open, lacey fabric just out of thread.

Lace making with bobbins

But you can create lace by simply making holes in already woven fabric. An early form of this so-called cutwork is reticella that was popular through the 17th century. Related to cutwork is drawn thread work where threads from either the warp (vertical threads) or weft (horizontal threads) of the fabric are drawn out to create holes, achieving a lace look.

The Pennsylvania Dutch enjoyed yards of handwoven linen in the homespun era and sometimes they used drawn thread to further decorate their embroidered items. Mostly commonly drawn thread was used in a panel of the ausgeneht handduch ‘decorated towel.’ These decorated towels used to hang on the parlor side of a door to the kitchen in older Pennsylvania Dutch homes. It is fairly time consuming and a bit nerve-wracking to cut away threads of fabric and remove them.

Removing threads and creating a fabric grid

Finally, thicker thread can be re-woven in to create designs.

Drawn thread panel on an ausgeneht handduch (1798), Schwenkfelder Library

A few years ago, I completed such a panel on a decorated towel for the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center in Kutztown.

Contemporary drawn thread panel on an ausgeneht handduch, PGCHC, Kutztown University

Henry Fisher’s book

The Pennsylvania Dutch loved to add decorations all over.

Mieleta, 19 September 2025

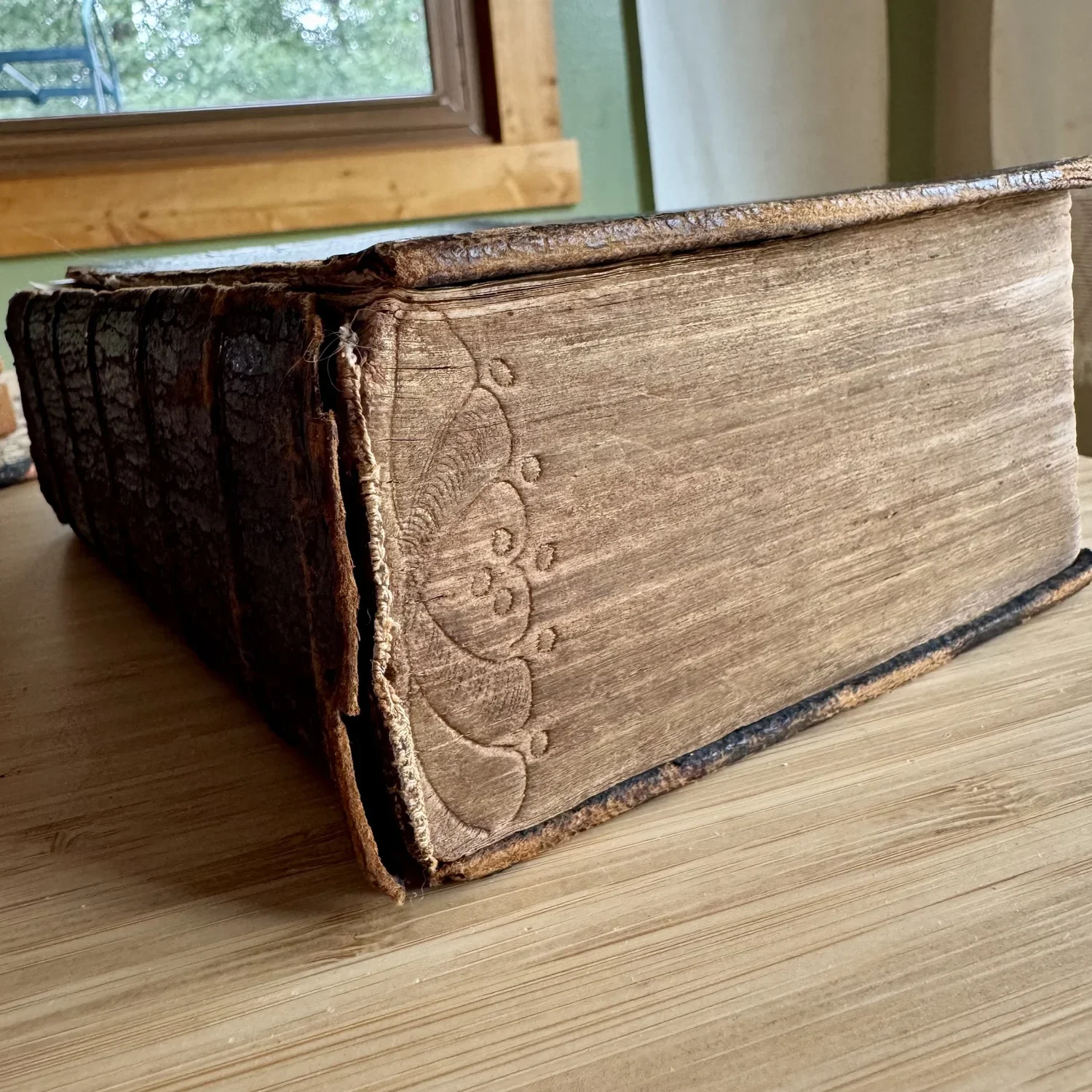

The Pennsylvania Dutch loved to add decorations all over. An old Bible in the Tuliptree Collection has a curious decoration on the tail edge of the textblock.

Decoration on the textblock

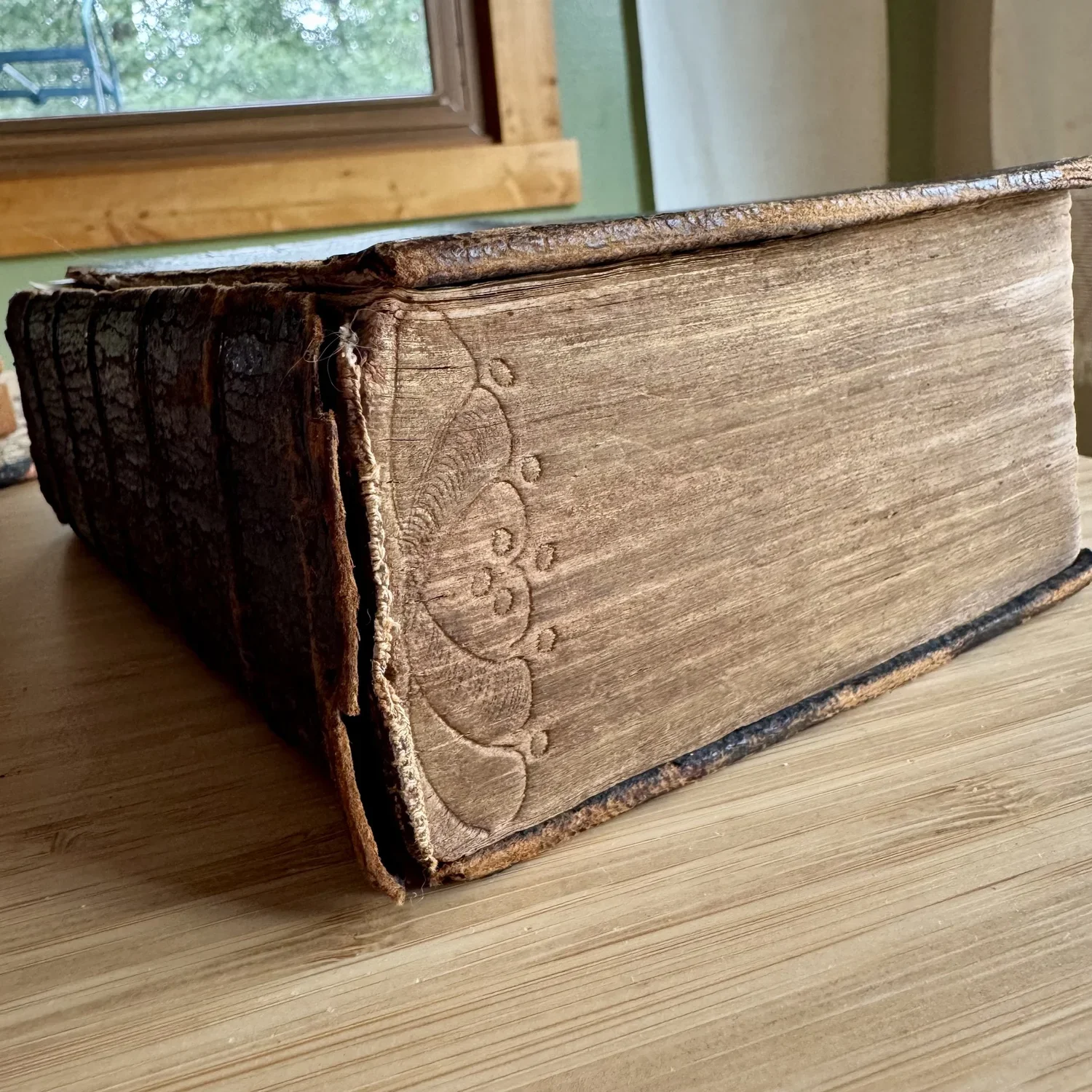

It’s a simple punch-type decoration with a sweet heart. We’re familiar with the common bookplate decorations of the Pennsylvania Dutch, but page edge decoration is more of an English practice. The Swem Library at William & Mary has a large collection of such fore-edge painted books. This book is certainly not English — it’s a 1782 Luther translation of the Bible printed at Halle, Germany.

Title page, Luther Bible, printed in Halle 1782

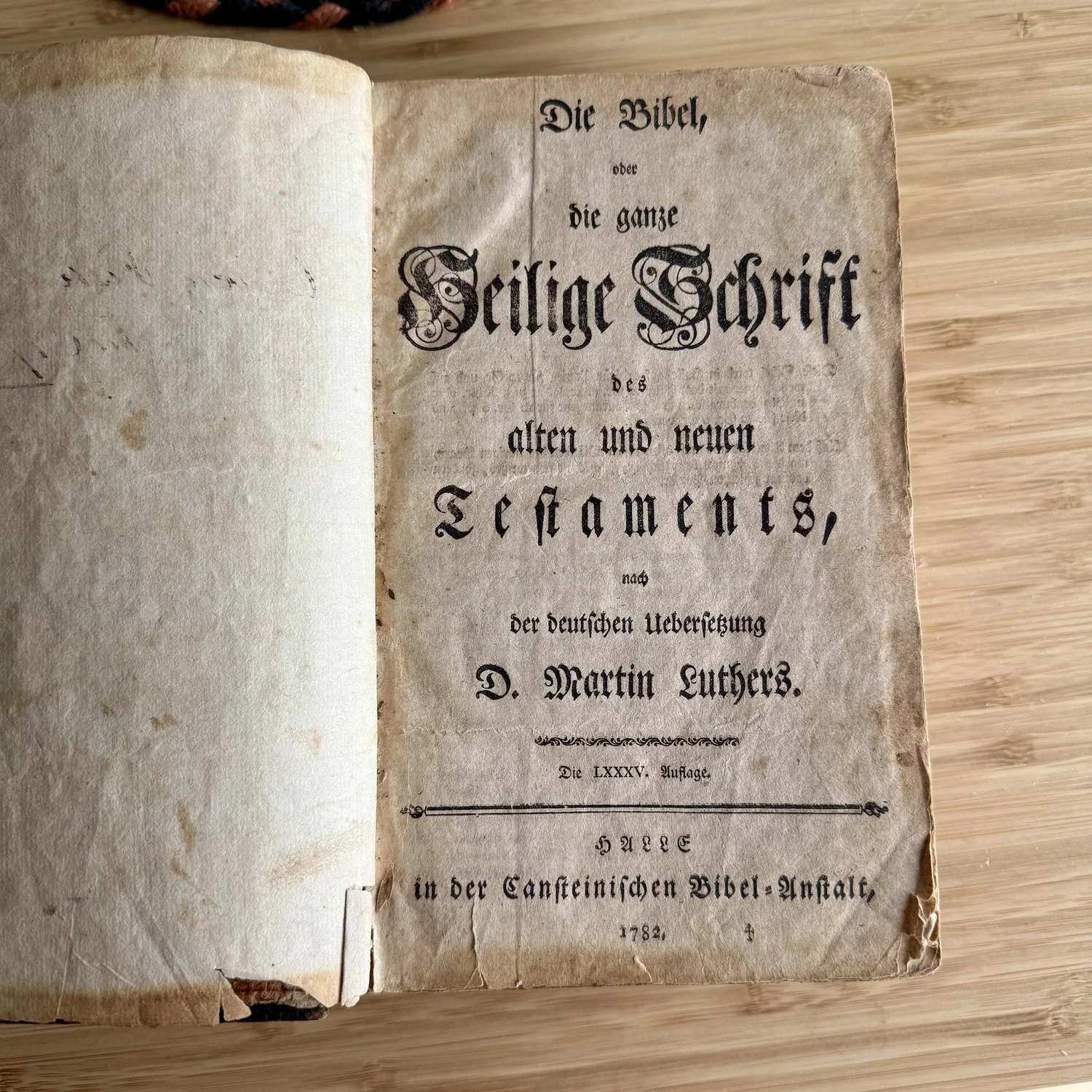

An inscription inside tells us who owned it.

Henry Fisher’s book 1784

Henry Fisher was born in 1758 in Lower Heidelberg (Berks County), the son of Johann Peter and Maria Appolonia (Heckert) Fisher, and moved to the Oley Valley, eventually buying a property there. Between 1798 and 1801, Henry and his wife Susanna Ruth had their beautiful limestone home built. It is an example of the growing popularity of Georgian house architecture among the Pennsylvania Dutch.

Fisher House, Historical American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress

Although it has classic Georgian characteristics, it was still built in the Oley Valley and so the carvings around the door, for example, are hallmarks of Pennsylvania Dutch craftsmanship.

Front door carving on the Fisher House, Historical American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress

Susanna Fisher died in 1821 and was the first burial in the new section of the Oley Union Cemetery in Spangsville. Henry, however, doesn’t rest next to his wife — in fact, he isn’t buried in Oley at all. In 1823, he visited his daughter Mary who had since moved 175 miles west. Henry died on that trip to Huntington County and so there he remains. Certainly, there was more than one Henry Fisher, but we can be more certain that Henry Fisher of Oley was the owner of Bible, because of a letter tucked inside. The letter was written to Mary’s grandson Norman by the daughter of Mary’s brother David who then occupied the Fisher home in the Oley Valley.

The Fisher home is still in the family and is located along 662 in Oley. They run a produce business, so stop by for some fruits and vegetables when you’re in the area.

Brickend barn decorations

There have been far too many heated debates about the purpose of decoration among the Pennsylvania Dutch.

Gottlieb, 12 September 2025

There have been far too many heated debates about the purpose of decoration among the Pennsylvania Dutch. Some say it’s “just for nice,” others point to deeper meanings — even back to pagan symbolism. I think, sometimes, it’s both-and. Things need not be in such a this-or-that oppositional stance. We can see this clearly in the decorations on brick-end barns.

Brickend barn with diamond decoration

In the middle of the 19th century, brickend barns increased among the Pennsylvania Dutch, as opposed to the usual wooden ones. They were more costly but made use of the burgeoning brick production of the 19th century.

Brickend barn with diamond/star and rectangle decorations

Barns need ventilation, but rather than just put in random holes between the bricks, some devised decorations that ranged from sheaves of wheat to humans. These new brickends presented a canvas for decoration and the Pennsylvania Dutch builders let loose their skills. I still have to make plans to see the famous man-riding-on-the-mule barn near Greencastle, Franklin County.