Tambour Yockel, part 2

Jerusalem Eastern Salisbury’s church records, kept in immaculate German script, suddenly end in 1791.

Tambour Yockel, part 1

In the years after the Revolutionary War, fear gripped tightly around the small Salzbarrick (Salisbury) area nestled on the slope of Lehigh Mountain.

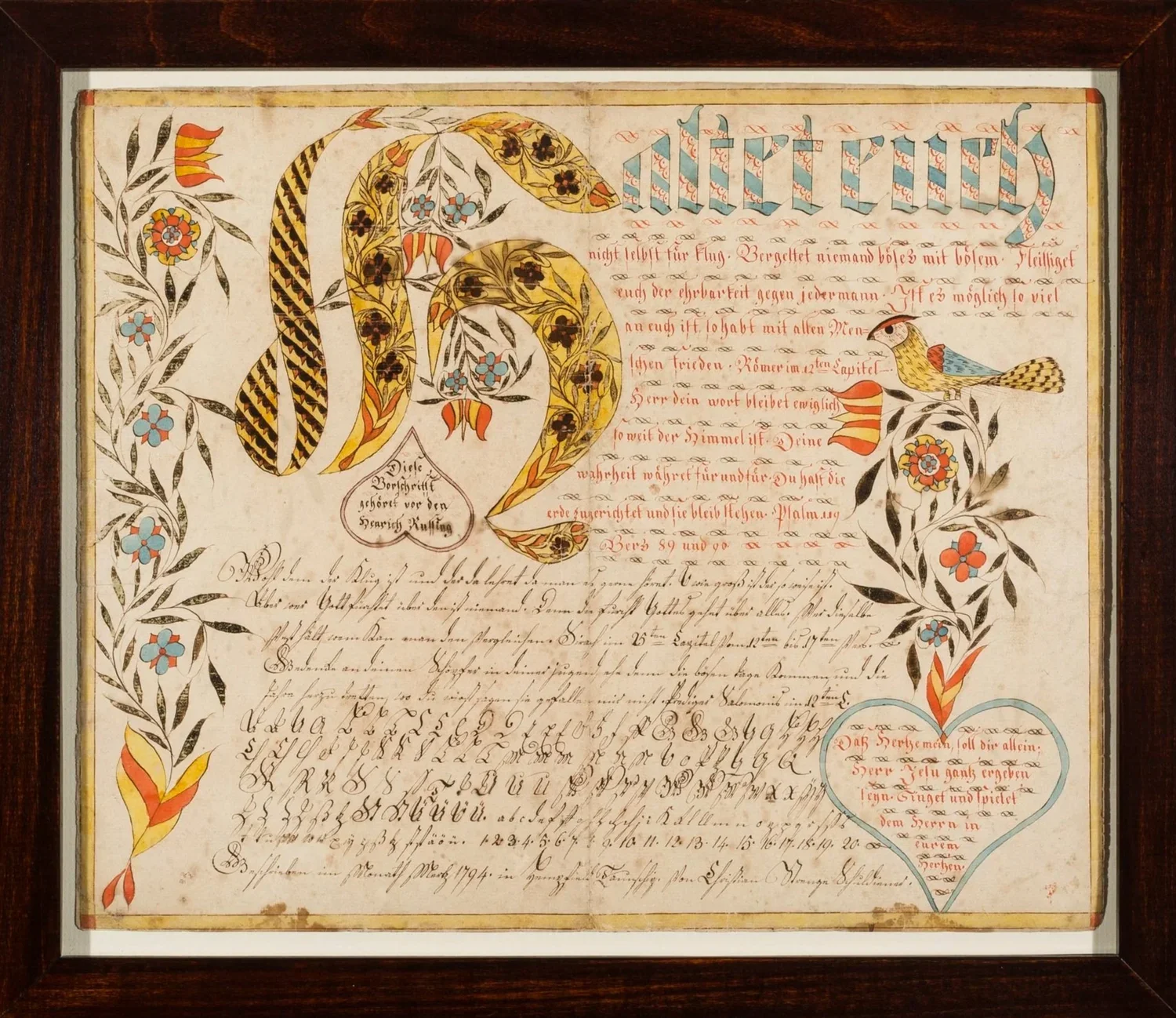

On the parade ground with fraktur artists

This past March, I returned to Marburg, Germany where I did most of my undergraduate college studies.