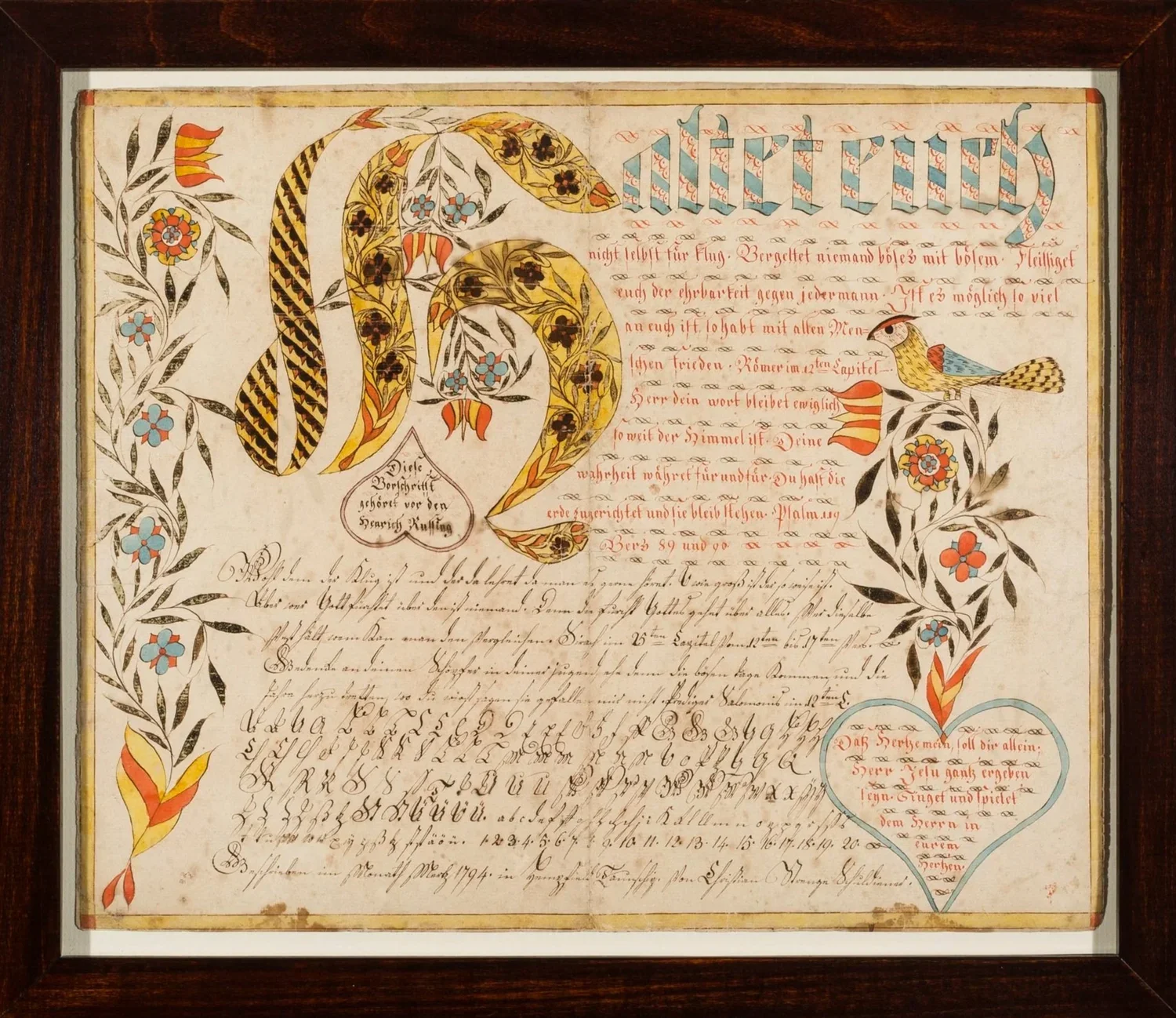

Borrowed and new

This past December I was commissioned to make a traditional Pennsylvania Dutch textile to celebrate the birth of a child — an heirloom to hang in the nursery. I decided on an ausgenaeht handduch ‘decorated towel'.

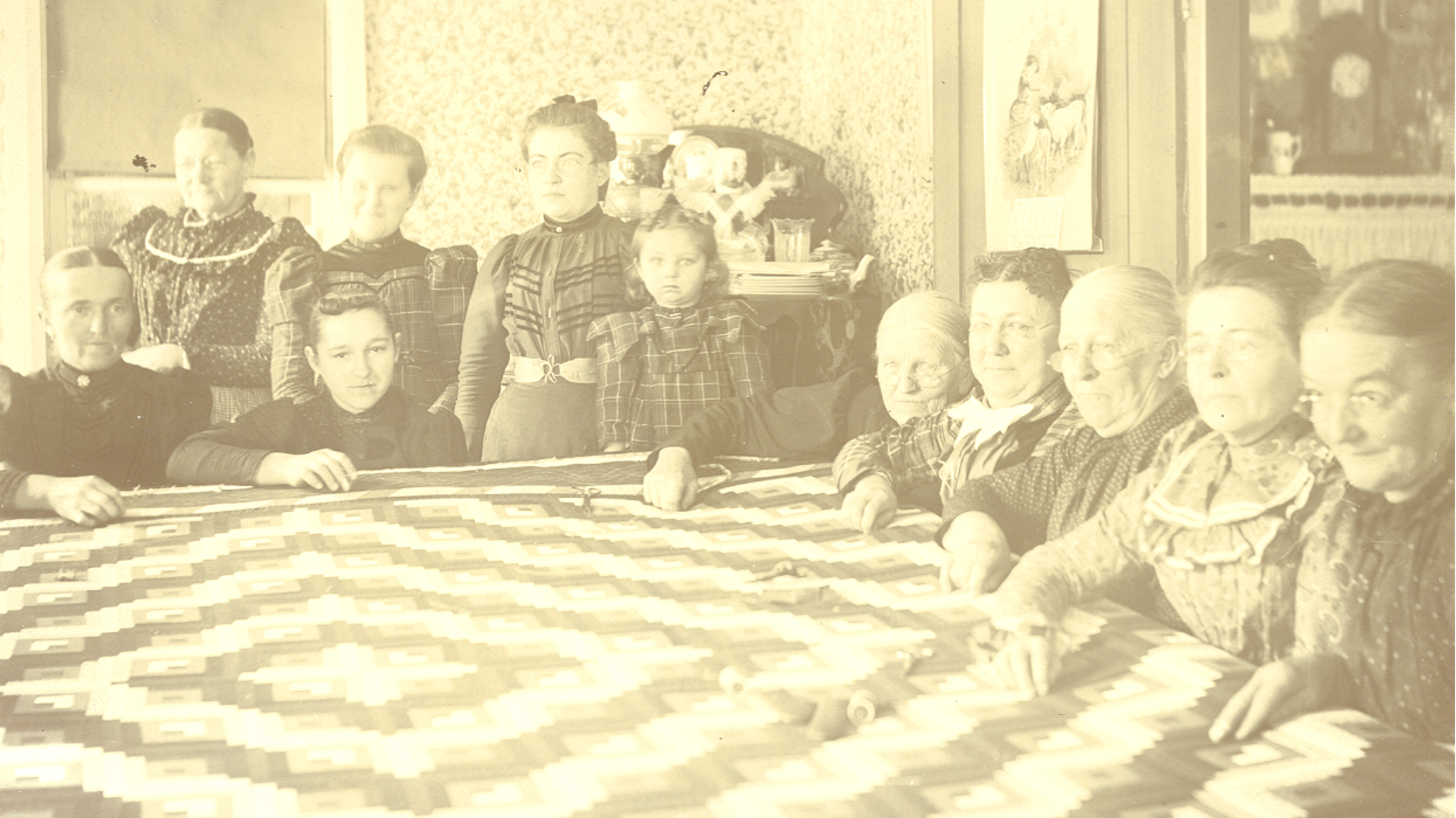

Dangerous quilting

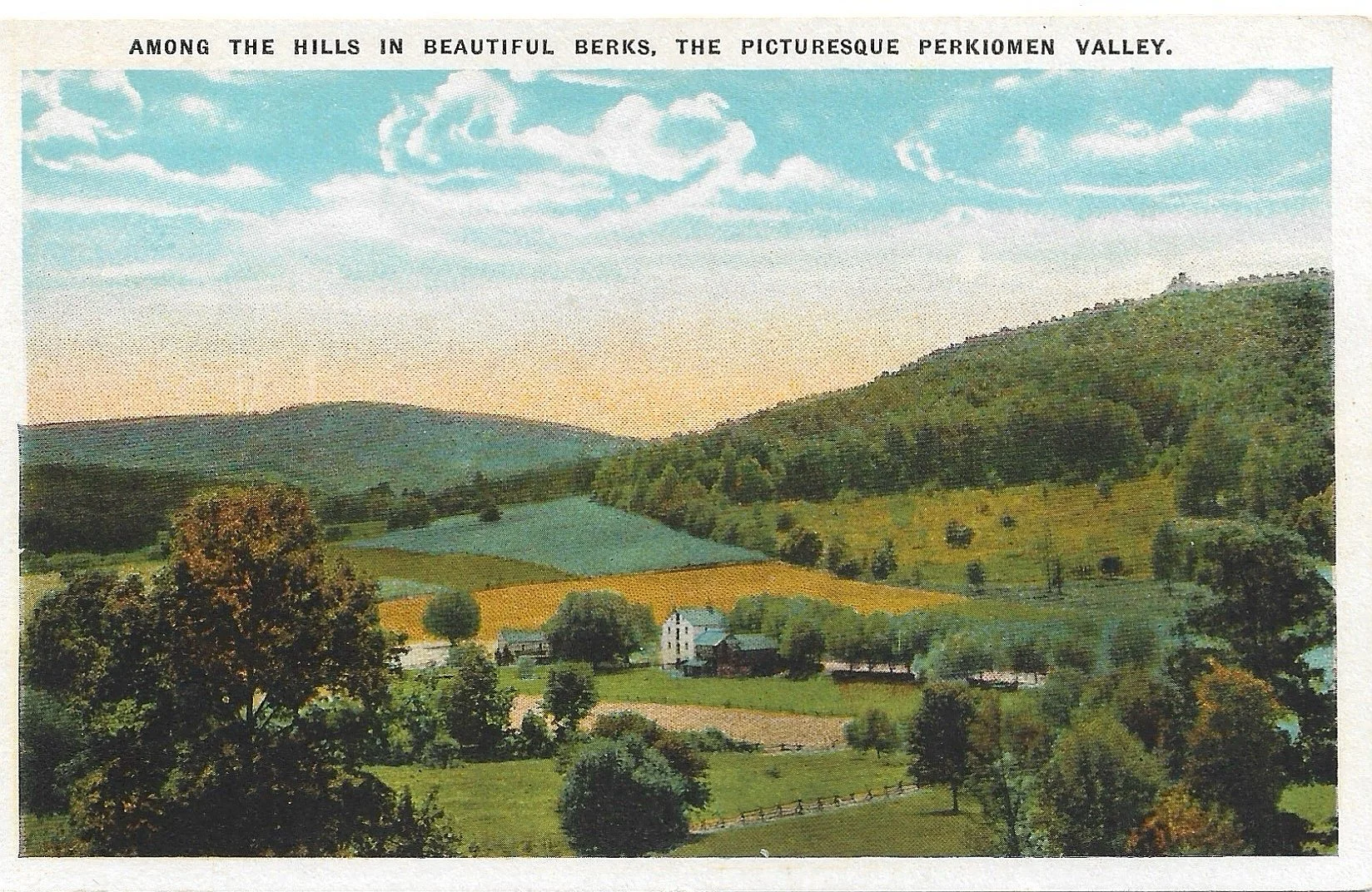

This week I’m starting on my Perkiomen Valley quilt pattern. As I started cutting out the necessary squares and triangles, I was reminded of a strange news report about a quilting party that happened this month 157 years ago.

To the Perkiomen Valley

As 2025 winds down, I’m thinking ahead to some craft challenges that I’d like to do in the new year. A few months ago, I finally bought a good sewing machine — nothing professional or super fancy.

Moravian candles

Bringing light into the darkness is a common ritual during the bleakest nights of wintertime. The Christmas Eve lovefeast in Moravian churches continues on this tradition.

Brickend barn decorations

There have been far too many heated debates about the purpose of decoration among the Pennsylvania Dutch.

West of the cloister

This week on my loom are some placemats in a pattern that I’ve called “Meadow Valley.”

On the parade ground with fraktur artists

This past March, I returned to Marburg, Germany where I did most of my undergraduate college studies.

Making bandboxes

This week’s post touches on two of my passions: collecting material culture and making material culture.

The wall at God’s acre

On a bitterly cold day in February 1784, General Peter Muhlenberg, enroute to Ohio, stayed at the Kucher homestead near present-day Lebanon, Pennsylvania.